Star photography has been a long-time enigma for photographers, and it still is for cinema-photographers. We can easily see a wonderful array of millions of celestial objects on clear nights,but photographing them has been difficult as they are pinpricks of light in a black sky and they are moving, so long time exposures are necessary.

There are four ways to shoot the stars, two have been around for a long time, and two are now possible with digital photography. They are: star trails; “one shot” star images; time-lapse photography and star tracking. I will address each technique, but there are a few consonants that are applicable to all four.

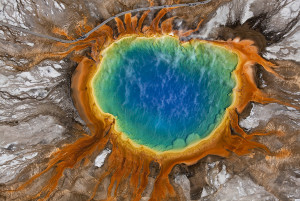

1. Altitude. It is not by chance that the major observatories of the world are at high altitudes. If you are at 10,000 feet, the atmosphere is less dense. The air is not “thinner”, but having less density in the atmosphere means that you can “see through it” better. Less humidity also helps, as there are fewer water particles to shoot through. This is why the desert areas of the American Southwest are favorite places for night sky photographers – 8,000 feet above sea level, clear and dry.

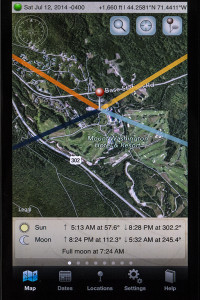

2. Light Pollution. More and more locations have extraneous light that “pollutes” the dark night sky and in turn “pollutes” your images. The atmosphere near cities literally glows on the horizon. The International Dark-Sky Association is fighting to preserve the night, but with more of us on earth it is an uphill battle. In addition, the airplanes flying though your frame near a city will not help to produce a “clean” image. To find the best locations for your photo of the stars, see Jonathan Tomshine’s Dark Sky Finder.

The moon will also affect your star images. The best star photography is done on a moonless, cloudless, still night.

3. Tripod. It may seem obvious, but a sturdy tripod is necessary. Set up the shot when there is still light, then come back to your tripod hours later with a headlamp or flashlight. Make sure the tripod is in a secure place, or your gear may walk.

Now for the four methods of taking star photographs.

Star Trails. These consist of concentric circles around the North Star (Polaris). They are almost always done with wide-angle lenses that capture the maximum amount of sky.

Prepare your camera for this type of photograph by going into the camera’s menu and turning off the LCD (saves battery power) and if you are NOT going to “stack” the final photograph (more on this later) turn the “high ISO noise reduction” feature on. Locate your eyepiece shutter. In some cases there is a manual one on your camera strap. If you do not have a remote release for the shutter, set the shutter release to a 2 second delay to eliminate shake. Set the shutter speed on “Bulb”. And make sure your camera battery is fully charged.

To take an image similar to David Harp’s Maine Coast photograph, locate Polaris and place it in your frame. If you want a terrestrial object in the foreground, make sure it is far enough away from the lens so that your focus will be on “infinity” regardless of the f-stop. Sharp tree leaves (as in David’s picture) are only accomplished on a calm night. Set the ISO on 400 and the aperture wide open (i.e. f2.8). Block the eyepiece and then open the shutter and leave it open for 30 seconds or so. Review the resultant image. Some stars will obviously leave a brighter trail than others. Look for the dimmer stars, as you want many tracks in this type of photograph. Make adjustments in the ISO and try another. If it is to your liking and you want longer tracks, decrease the ISO and lengthen the exposure.

Some photographers want longer tracks but not the long exposures that produce “noise” in their pictures. They take many shorter exposures (with the noise reduction camera software turned off) and then “stack” the images in Adobe After Effects or Photoshop.

One Shot. Higher ISOs on today’s digital cameras (Sony’s A7 has an ISO of 409600!) allow photographers to capture the night sky with very little movement in the stars. The more sophisticated cameras combine high ISOs with noise reduction to produce “grain-free” pictures The camera preparations are the same as for photographing Star Trails.

Here is how to make an image similar to the one of the Chess Queen and the Milky Way. It is almost imperative that the one shot star picture has a foreground subject. You can find one in the daylight, but the very best of this kind of image has the Milky Way in it, as this part of the night sky is very arresting in a “one shot”. The Milky Way is a look at the edge of our galaxy, where many, many stars are “stacked”. You need to see it to position it in the frame. Lighting terrestrial objects can be a challenge, especially if they are a distance from the camera. Also, very little light is needed to expose these objects, as your ISO and exposure will be set for the stars. For the Chess Queen, a flashlight with 3 layers of tissue over the light was used, and the formation was “painted” for only a part of the entire exposure.

Set your camera to 3200 or 6400 ISO with the aperture on your camera wide open. Take a 20 second time exposure painting the foreground. Sophisticated cameras will spend another 10 seconds or so to process out the noise. Check out the resultant picture. Too much light on the foreground object? Not enough stars? Adjust the length of the exposure, but try not to go beyond thirty seconds or you will get noticeable star movement.

Time Lapse Skies. Video has a difficult time with stars, because to capture motion the video cameras expose 30 frames a second. Eventually the ISOs and software will allow it, but for now time lapse is the way to go. I won’t spend much time on the technique in this blog, but with high-end digital 35mm cameras, tracking devices and post processing, a compelling moving video can be made. Dustin Ferrell has been a pioneer in this technology and he has shared his expertise in a web tutorial. The second part of the tutorial is a technical treatise on post processing the images, but the first part displays his results and they are spellbinding and worth watching.

Piggybacking on a Telescope. You can make a photograph by shooting through a telescope, but perhaps you are an astronomer creating an image rather than a photographer with a camera.

More sophisticated telescopes use motors and computers to track celestial objects. If you already have a telescope on an equatorial mounting and you know how to correctly polar align the mount, you can let the camera and lens ride piggyback on top of the telescope and shoot longer-exposure wide-field photos.

An equatorial mounting has one axis-aligned parallel to the axis of rotation of the Earth and is called the polar axis. The other axis is called the declination axis. This axis allows movement of the scope at right angles to the polar axis. Movements in these two axes together permit aiming the scope at any part of the sky. Once an object is found, both axes are locked down, and just the polar axis turns to track the object. Got it? If you are REALLY interested go here.

As primarily a still photographer, perhaps you can find an astronomer and ask him politely to piggyback your camera on his telescope.

Using a Remote Telescope. Many telescopes around the world allow you to buy “telescope time”. You can determine what part of the universe that you want to be photographed and what object. But how can you contact them? Here is a link to the website Telescope Guide where you can learn how to contact observatories to capture your desired image. The website will guide your request so that you receive the best results. As a rule of thumb, most basic image requests using remote telescope operators will use 5 – 40 minutes of telescope time to capture your image. The observatory will give you a range of your costs when you specify the subject matter, but rarely will the charge exceed 30 USD..

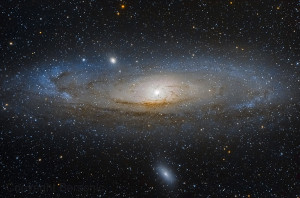

Photos of outer space are fascinating! NASA has a website that features an “Image of the Day” gallery. On July 30, a high school student, Jacob Bers, took the Image of the Day -Andromeda, a “nearby” galaxy. It has hundreds of billions of stars. OK. Enough of having our minds boggled.

Experiment. A few nights ago, there was a moonless, still, clear night behind my house. I face 500+ acres of open space with no lights, so I set up to shoot the stars over an island. To my chagrin, when I went out in the middle of the night to photograph, clouds had moved in. Since I was already set to shoot, I went ahead. To my surprise, the island and clouds were illuminated by a distant marina (by the long exposure), but you can still see the stars!

I hope this blog will help you when you see the starry night and say, “I wonder how I can photograph this?’

Want to tap the expertise of a National Geographic photographer? Consider joining me on my upcoming workshop in the Serengeti. The cost has been reduced for last minute sign ups.