Artificial Intelligence And Photography

The Good and the Bad

In this blog I will illustrate the exciting advances with AI, specifically the image directed applications such as Dalle -3, Gemini, Midjourney v6, and Claude. I will also reference applications that work directly with your images such as Topaz Labs and Adobe Firefly within Photoshop.

Later I will address the downside of AI for professional photographers, namely how it diminishes their viability as it dilutes the marketplace, causing loss of income and stifling innovation and creativity.

Any tool that helps you expand creatively or drastically reduces the time it takes to generate possible creative solutions are welcomed additions to your photographic quiver.

I would like to introduce you to Pablo Corall Vega, a photojournalist that has taken portraits of his subjects and using AI, turned them into art.

Pablo says, “The arrival of digital intelligences has pushed me to write again. Why is this moment — the emergence of a new generation of AI — seen by many as one of the great turning points in history? Because never before have we had the opportunity to converse with a non-human entity using human language”

When queried about whether he asks his subject to agree to appear in an AI image, he says that because his subjects would never recognize themselves in the final product he doesn’t ask for their permission.

One more from Vega:

“What makes us unique — what distinguishes us from the machine — is the experience of life. Not just the narrative of life, but life itself,”

Pablo Corall Vega

What we mistakenly call Artificial Intelligence today is generative machine learning, there is no such thing as AI intelligence. It is a form of machine learning, combing the internet to construct a summarization of correlations.

The U.S. Copyright Office May 2025 publication, Copyright and Artificial Intelligence Part 3: Generative AI Training, a 113-page footnoted document, gives a short explanation of how it works,

“Machine learning is a field of artificial intelligence focused on designing computer systems that can automatically learn and improve based on data or experience, without relying on explicitly programmed rules…Generative AI relies on a subset of machine learning that builds models using neural networks… Modern neural networks are capable of computing highly complex transformations, such as the conversion of text to video. making small adjustments to the weights in a direction that improves performance—sometimes analogized to tweaking and turning “knobs and dials”—the network approximates or “learns” how to transform inputs into expected outputs.”

“…In practice, models estimate probabilities for “tokens” rather than words themselves. These are numbers that are pre-assigned or “indexed” to particular words, pieces of words, or punctuation marks. Because neural networks are mathematical functions, text must be converted to a numerical format for processing… Simply providing these models with natural language directions and then using them to iteratively predict each next token led to surprisingly good results…The same general principles apply to generative models for other types of content such as images, video, and audio.”

Kira Pollack, who formerly held positions as art director of Time. The New York Times Magazine, and Vanity Fair, is now a distinguished fellow at Starling Lab for Data Integrity. She spoke at the annual meeting of The Photo Society and showed groundbreaking work at Starling using AI to manufacture captions for images that have none. The captions not only bring to light what is happening in to photographs but also include mood and intent. The rationale behind this work is to build an archive for the future. She says, “The photographers of our era took the great risks to create these vital documents of history. We risk losing not just the images but also our ability to bear witness to history itself.”

Kira also highlights other efforts to use AI to create databases of text to image, including photographer Edward Burtynsky who has been pioneering a solution to one of the greatest challenges in preservation: scale. Burtynsky developed a high-tech scanner designed to digitize and catalogue images at an unprecedented rate — up to 2,000 per day. What used to take years can now take months. The system functions like a precision turntable, scanning both sides of prints simultaneously with high-resolution cameras and synchronized strobe lighting.

Algorithms powered by artificial intelligence then extract handwritten notes, metadata and important details, organizes the information so each image can easily be searched by keywords and includes a clear description. So far, Burtynsky’s team has digitized a vast collection of images about Canada for the Image Center, a photography museum in Toronto, and 89,000 First Nations and Inuit drawings from the Toronto area’s McMichael Canadian Art Collection. “I call it unleashing history,” Burtynsky says. “There’s all this history that’s locked up.”

Up until now I have been addressing OPS (Other Peoples Stuff). It’s time to talk about how AI can affect your own photography. You can use AI tools to rescue images where you made capture mistakes, e.g. blurry, out of focus, inadequate exposure, poor resolution, excessive noise, etc. For illustration purposes, I will use Topaz Labs tools as at this time they seem to be on the forefront of this revolution with what they call “essential image and video enhancing tools.”

First, here’s an example of their blur sharping tool that I used on an image of a boy sledding down a hill.

Topaz has processed more than two billion images. They include updated models where algorithms analyze images that their users (including you) provide them by using their products.

Screenshot

Their premier product is called Gigapixel AI, where the user can upscale a low-resolution image up to 6X. Following is a screen shot of the Gigapixel AI dashboard showing sliders and radio buttons for real-time adjustments,

I picked this particular photograph to show that although Gigapixel AI did a great job on the faces from the original on the left to the enhanced version on the right, note that the anchors on my shirt did not translate as well. There is still something to be desired, but we can now say that it’s hard to take a bad picture.

I want to spend some time on the detrimental aspects of the relationship of AI to photography. In the U.S. Copyright document that I referenced earlier, here’s several issues that the report includes – 1. Lost sales, 2. Market Dilution. 3. Loss Licensing Opportunities.

From the report: “The copying involved in AI training threatens significant potential harm to the market for or value of copyrighted works. Where a model can produce substantially similar outputs that directly substitute for works in the training data, it can lead to lost sales. Even where a model’s outputs are not substantially similar to any specific copyrighted work, they can dilute the market for works similar to those found in its training data, including by generating material stylistically similar to those works.’

The assessment of market harm will also depend on the extent to which copyrighted works can be licensed for AI training. Licensing is already happening in some sectors, and it appears reasonable or likely to be developed in others—at least for certain types of works, training, and models.”

To illustrate how loss sales and market can come about, here are several prompts (queries) to Gemini, Google’s AI phone app and the results.

Premise, I own a horticulture publication and want to show plants that we have to offer and include a person for scale.

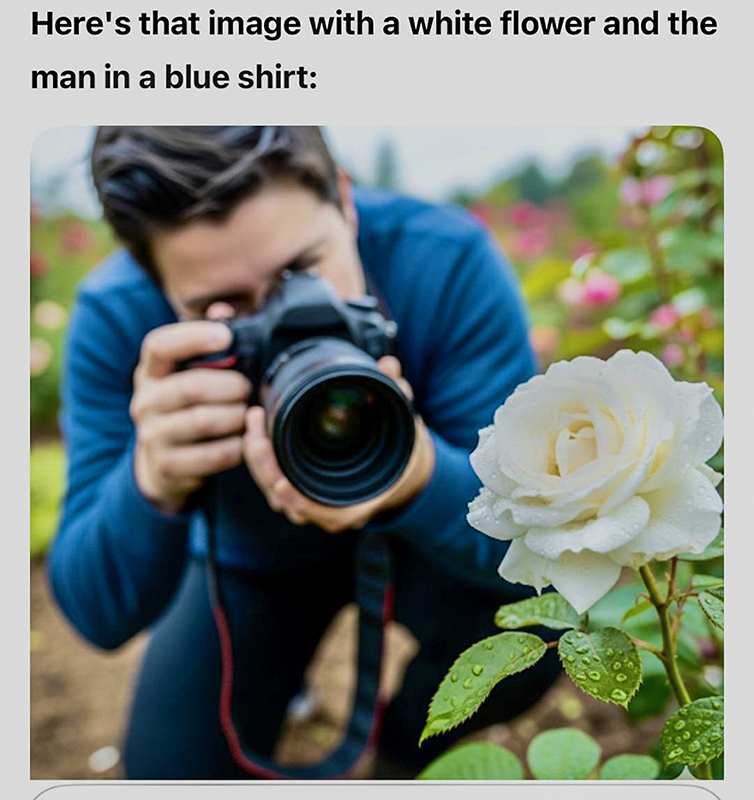

Now I want the flower in white, and I think the man’s shirt is too dark.

Of course, neither of these images are photographs and they took about 15 seconds for Gemini to produce them. And I can change the flower to any species that I want to feature.

But wait, I’m now a publisher of a wine journal and I want to show my readers the effects of the spotted lanternfly, an invasive species damaging vines in vineyards. Just change the prompt,

Both of these examples can be used by the publisher without compensation to an illustrator or photographer and they know what they are getting without hiring a real person to create the image for them.

Both of these examples can be used by the publisher without compensation to an illustrator or photographer and they know what they are getting without hiring a real person to create the image for them.

As pointed out previously, some large publications are making licensing deals with Artificial Intelligence entitles, sharing their content with them in exchange for using the AI tools. But what about individual photographers like you and me who don’t have the resources or clout? Fortunately, there is an open-source consortium called the Content Authenticity Initiative who are working to embed information in the original digital capture so that if stolen, one can prove in court that it was created by the originator.

They want to establish an open standard for authenticity and provenance that can be attached to images, video, audio files, documents and more. Camera manufacturers are already including it in their high-end products. At this time, it’s a work in progress, but it gives individual photographers hope.